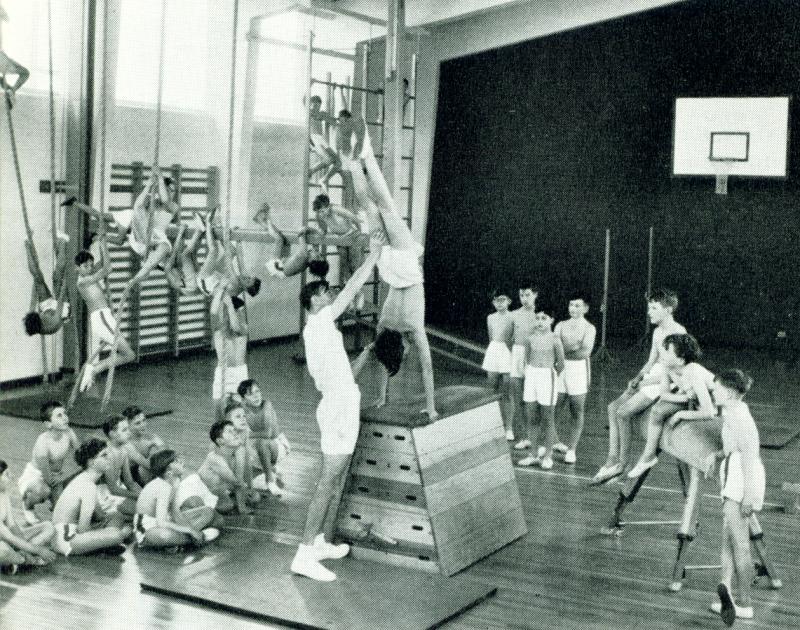

Burnley Grammar School

8085 Comments

Year: 1959

Item #: 1607

Source: Lancashire Life Magazine, December 1959

A good informative post Nathan.

If I'm honest about it though, it does surprise me that schools are still doing the whole skins versus shirts thing in PE in this day and age. It was always quite a divisive thing at school I found. I say that as someone who had no problem taking part in PE with my upper body out on view shirtless. What I remember about doing this myself in school is that there were never many enthusiastic takers for being on the skins teams, I never openly volunteered it and I wasn't ultimately worried which side I was on. My school had a collection of hockey and netball bibs that were used a lot for both boys and girls outside. They could have just as easily been used inside when we did some of the team stuff there too like basketball, indoor football, softball etcetera. They kept ours in a cardboard box very close by our gym and quickly accessible along with other bits and pieces such as actual spare kit. I wonder Nathan if you also have bibs available. But inside teams always went down the skins versus shirts rule. I preferred it when the whole class just discarded our top and were the same rather than split into have's and have nots. The choosing in PE just who was going to be a skin and a shirt was sometimes an irritating and slow timewasting task, leaving someone unhappy about it.

What Nathan says here - 'I'd have no interest in making anybody do that who was uncomfortable doing so.'

This is the difference between a modern PE teacher and one who took us forty, fifty, sixty years ago in schools, probably even just twenty or thirty back too. PE kit was non negotiable and I'm sure others will agree on that. Just because I might be uncomfortable doing PE shirtless did not stop me doing PE with a bare chest. Asking not to would have been met with short shrift, and nobody would seriously expect a plea of awkwardness to be met with a backdown from the PE teacher, far from it. This in my school was most noticeable not with shirtless PE but with the naked shower requirements for everyone. There were pleas from boys to avoid those and not listened to and fell on deaf ears from PE teachers who were not concerned too much about who felt uncomfortable or awkward doing these things. So quite a big difference in attitude between then and now.

I was struck by the very clever subtle language on showering nowadays, no longer saying such things are compulsory like in my older school days but saying they are 'expected'. Quite clever word play that and I note that it still has the same effect as being old style compulsory.

So from what I understand Nathan, you do sometimes still tell boys in your PE at school that they are to remove their top and go barechested in PE, and it goes okay like that, but if someone did kick up a fuss about it you'd back down and not force the issue on them. It's sort of how I read what you say here.

I think what you've stated there Nathan is broadly what I would have anticipated you might have said. I don't think anybody should feel surprised by anything there.

Nathan - many thanks for your interesting comments

Thanks for the comprehensive answer Nathan.

Gary you said: "Would a PE teacher be frowned upon if he chose to take his class all shirtless regularly nowadays if the school generally didn't do that, or would he even be allowed to do it. Questions, questions!"

I can answer your question, and I'll answer the last part first.

The answer is a firm and definite yes, I am allowed to do that, nothing at all prevents me for example telling pupils to strip down for team shirts and skins games. They remain a popular feature in PE. There is nothing at all to stop me asking a class to do those things. It's my decision alone on a class by class basis. I lead PE classes frequently which within them have pupils in bare chests in various situations. There are no hard and fast rules in this unlike some of the schools older people went to long ago where things were set in stone and everyone knew what they had to do.

The old style PE many older ones here took long before I was born always seemed excessively regimented and very standardised. It does not surprise me that many hold their own PE in low regard but I think there is much more understanding of wider issues nowadays and more actual listening than there might once have been if you are now say 65 looking back to your own tougher time with it.

Many boys who think they are great at sport such as football nowadays in school have parents who see potential multi millions from a sporting career, something unheard of even for those who really did make it once upon a time.

But I do agree that if as teacher I became a stand out against the grain in a school like mine and was the only teacher who always took boys PE and never let them stick their PE kit tops on then it might well raise a comment but as I've never done so I can only presume that would be the case. I wouldn't wish to do that however. I'd see no real benefit in a blanket decision saying everybody had to come to my PE class in school in a bare chest. I'd have no interest in making anybody do that who was uncomfortable doing so.

But the upshot answer is I could do so if I wanted. I'd only have to answer to my immediate PE department boss if I wanted guidance or he had something I was doing drawn to his attention by a third party pupil/adult.

I think we have a good balance currently. All pupils at some point will do some PE in a bare chest under instruction to do so and there are no open issues with it that I've yet become aware of. Majority PE is in vests/t-shirts/sweatshirts.

I'd also remind you that our school does take showers after PE. They are not described as compulsory, but as expected. In practice everyone does unless told otherwise due to serious time constraints or lack of real need. That's uncommon though. Sometimes a late lesson can just be allowed to clear off.

Just incase anyone has also forgotten about a previous comment I made about taking swimming at our school, we had somebody wish to swim in an all over lyrca style modern full body suit but the decision was made that we would not allow that and traditional swimming gear should be worn only. That was very unusual though.

So yes, if I was so minded I could make all my PE classes go bare chested but I would very likely have to justify my decision, whereas just doing so now and again is the normal situation and not even worthy of comment from anyone, apart from on these historical pages that interest the readers here.

Comment by: Neil Warnock on 21st May 2023

I had to take showers at both my middle school and secondary school.

What rotten luck that was. A double dose. Middle school had no need to do that but if it worked out for you who am I to argue.

Some of the men on here will now be wondering if they had a Julia & Co making notes about them won't they.

Quote - "What's the point of gym vests indoors?" says William.

Fair point. But I'll turn this one on its head too then - what was the point of NOT WEARING a gym vest going OUTSIDE on cross country?

Hi William, my own skinny body had to be exposed in school so many times against my will and I rather resented any teacher having that power over me. Perhaps kids like me were another one of these silent majorities on an issue. A shame we never got to vote on it if so.

Tanya that is a very hard question to answer.

I probably shouldn't admit to this on here as it will add fuel to those males who felt rather unhappy about their lot in PE class. I went to a mixed secondary school early eighties which spared the boys no blushes when it came to sharing PE with the fairer sex. From the two PE classes we took each week, one would frequently be a shared gym one up to the age of fourteen in which many boys, if not all of them did not come along in a top, turning up primarily in white shorts alone. Many boys were actually very skinny, I didn't mind that. I have still got a tiny little purple notebook I had at the time where I and another two girls secretly rated the boys we liked out of ten based on many characteristics, personality, how they dressed, what their hair looked like, their voices and body type, including how they looked with much of their clothing off as we saw them in PE. I'd like to reassure any of you less than confident males out there that we were actually very complimentary and not unpleasant to anybody really. It never crossed my mind what boys in PE thought we might be thinking of them and their bodies when we had a chance to look at them closely and I would never have dreamed of saying anything openly to any of them, except in my tiny notebook I shared with two close girlfriends from school. I was one of those young girls at school who didn't like the over confident cocky type of boy who loved himself and was vain but found the quieter sensitive ones more to my liking and the physical body was never the most important thing either, it was personality, good manners and a nice smile and sense of humour.

Tanya, Good question! Less washing for mothers, perhaps!

Gym vests were on our uniform list (grammar school 1960s) but we never wore them. I was quite shy about my skinny body but, oddly, being bare-chested never bothered me and I am surprised at how much the practice seems to have troubled some of the contributors to this discussion.

As for the reason, can I turn your question on its head: what would be the point of gym vests indoors? At my school the idea that boys would have been shy about being bare-chested would have been ridiculed. We were expected to get on with it; after all, we swam without tops. I benefited from having no choice because it made me realise that something I thought I would dislike was fine. Same applied to no pants under shorts and nude showers.

Adding to Bill's earlier question, I'll simply pose a simple question - what actually is/was the purpose of boys being barechested rather than shirted in a PE lesson. Any takers on that one?

Gary, you're right it does take some longer than others to adjust to being barechested and it's something that hasn't been touched on much. I had a couple of friends who initially weren't happy with the school's stance but after around 2/3 months got used to it and by the second year preferred going barechested. I kind of got thrown in the deep end doing boxing lessons which for me was a good thing.

While middle school is getting a mention here and throwing back to the barefoot running while I'm at it, at both my own infant and middle school nearly always during PE in the school hall the lesson was done in our bare feet, not even plimsolls. So I was very used to that and when I arrived up at comprehensive at twelve we wore trainers in the gym which actually felt overdressed. But ironically while at the lower two schools we also always wore any type of t-shirt of our own, no defined rules what it had to look like, whereas on entry to comprehensive although I now wore trainers in PE I suddenly found I no longer wore a top in that school's gym 90 percent of the time there. I think it was purely down to teacher choice that we did our PE like that.

Would a PE teacher be frowned upon if he chose to take his class all shirtless regularly nowadays if the school generally didn't do that, or would he even be allowed to do it. Questions, questions!

In answer to your question Bill, I think boys going shirtless if they are having to in school is an acquired taste I think, something that certain boys slip into far easier than others. I don't even think it's based especially on how anyone actually looks is it. I do think age plays an important factor here though.

Well, this is a emotive topic for some so here's my first experience. My mum thought it a good idea start boxing lessons. That first Saturday morning I remember going through the doors with my mum and guided into an office. Soon after my mum was happily chatting away with the owner one of the coaches turned to me and told me to show my chest. I didn't have a clue what he meant until mum sharply said "shirt,vest off...now!" After a quick look at my chest and back and a couple of questions later we were taken into the hall and all the lads were barechested, most doing exercise, a couple of 14 year olds were fighting in the ring. We joined a few more lads of a similar age watching on for a few minutes before I joined a couple of recent arrivals and started exercising with them. I don't remember much else about that first session apart from being totally done in at the end! A couple of months later my primary school introduced barechested indoors PE for all boys without exception, the official reason being "to ensure all boys are prepared for physical exercise at secondary school" - did it really take 4 years though?!

I had to take showers at both my middle school and secondary school.

I was very unhappy when I started middle school in 1974 and was told to do this as part of PE in that school. I remember it being a proper naked shower in a communal setting with only cool water. I can still remember the fear and surprise I felt the first time I did it and all the friends I was with just unexpectedly finding ourselves naked with our willies out among each other which was a very weird sensation. I didn't want the teacher watching me like that.

School could be brutally demanding like that even at that young age. I think I told my parents I didn't like it but was told not to be so silly or something like that. We, my class and I, seemed to shower most lessons throughout middle and secondary schools. Our naked bodies were not seen as anything to feel private about or shy with. For boys anyway.

Later on when I started at secondary school in 1978 the showering at that school was nothing like the deal I'd made of it at middle school, I'd been conditioned to accept such things took place already and dealt with it, saving me the anxieties that some who get thrown into secondary showering at that age for the first time face.

I'd quite like to understand what is the real problem for those on these pages who take issue with the barechested PE requirement they had to undertake when at school. What is the actual issue with it exactly, nobody ever quite seems to manage to say it.

It might well be, Robbie, that, having read the experiences of others, and having obtained maturity, they now question the somewhat dubious behaviour of teachers of the past. These days some of those teachers would find themselves in court and facing custodial sentences - those, that is, who had not run away to South Africa and been fighting extradition for years, because they are too frightend to answer for their behaviour in a British court.

'Full on nudity was just so regular and normal and unremarkable in those days at school.' - Gaz.

This is just so very true. A lot of people seem to have seen things in a completely different light now they've got older. Some people are wanting to find problems with it that didn't really exist for the most part.

I don't know whether it's still a thing nowadays or whether it's something that's died out over the years but at school kids were often given the bumps on their birthdays back 40 or 50 years ago. This seemed to happen lots to those who didn't like that sort of thing much who would find their arms and legs grabbed. I remember getting it once. Mostly it was done in good humour and without malice.

In our school the boys and girls changing room doors were directly opposite each other barely eight feet across a corridor. You could always hear the going on in the other changing room. One of the quieter boys we had in our class was given the bumps actually in the PE changing room on his birthday, something like 13th, 14th I'm unsure which exactly. He was also in his birthday suit. Full on nudity was just so regular and normal and unremarkable in those days at school. But on this day I felt so sorry for the lad because the birthday bumps wasn't good enough for them and they kept hold of his arms and legs and the door flew open and he was delivered across and thrown through the girls changing room a few quick feet away and their door was then held shut for a few moments. I have never heard screaming and shrieking so high pitched and loud in my life as I did then. But my school was a bit of a basket case with things like that happening all the while right under the noses of any given teacher.

Reading this thread has brought back some unpleasant memories for me.

On the subject of showers, we had the walls with the shower heads along them and were expected to stand there in all our glory at the end of PE. Often the PE teacher would stand at one end watching. I felt uncomfortable with that at the time but now I am thinking perhaps there was something quite sleazy about that and have knots in my stomach just thinking about it. (There were rumours about that particular teacher but all those years ago you didn't really imagine your teachers were gay (a word not used then, but I am trying not to offend anyone).

I grew up in a very repressed household so stripping off in front of anyone, even my close friends was purgatory for me. Looking back, I am horrified at the complete lack of respect shown to school pupils at what is their most vulnerable age range. I would still not shower in a communal area. It's hard to now believe we used to be herded about together naked like that during part of the school day without the right to refuse and simply say, no. It just seems to me that it is a very personal thing and I should be entitled to privacy. I have addressed the issues of nudity and my household is very different from the one I grew up in.

As for bullying, I was bullied unmercilessly at home by my older brother. On two occasions I had problems with girls at school but frankly their bullying did not match my brother's by any stretch of the imagination. I just used to ignore them, which I know wound them up even more but the only positive side of living with a bully was that you were fairly immune to what anyone else threw at you.

I have learnt that bullies only bully those they get a reaction from. Once you stand up to them, their satisfaction is removed and they usually stop. Unfortunately, they usually just pick another target.

My friend's daughter was bullied by one of her peer group when she was 10. After months of inaction by the school (the bully was well known as such but the school still did not stop the situation) the bully found the end of her victim's tether. She went up behind her and pulled her hair. My friend's daughter turned around, paused, then knocked the bully clean of her feet and across the playground with one blow. (It was seen by a dinner lady so we know it is true). She was never bullied by that child again.

I finally stood up to my brother last Christmas (I'm 43). His bullying had changed into a lack of respect and he too found the end of my tether. So far the change in him has been quite startling and his attitude towards me is different. It remains to be seen whether it lasts.

Shouting at the teacher like that and getting away with it is the difference between being at school in 1998 and being in school in 1968. You would never have got away with that when and where I was at school I can confidently assure you.

I'll grant you had an interesting outcome there and I'm not saying you were wrong.

If I didn't call my teachers Sir at the end of every other sentence there would be trouble. Total unconditional respect was expected - whilst they of course just referred to us all by surnames, like a previous comment mentioned, and that doesn't exactly convey respect in both directions does it.

What a brilliant story that is. I wouldn't have had the nerve even if I was inn the right. Good for you.

Greg2.

That story of the quiet boy fronting up to the teacher so relates to me.

Now I only left school quite recently compared to others here, in 2001 and am only just turned 40. However, just like everyone else much older than me whose secondary life was mainly late 90's, school did the showers thing most PE lessons and although the majority of PE we wore our various tops, every term some barechested PE would crop up at some point with team sports or something else.

Now all my PE teachers were okay, except for one who in my considered opinion I thought didn't like me very much, Mr Hart-Booth his name was, and was forever giving me attitude I didn't think I deserved and I felt I could never do anything right no matter how hard I tried with him. He was only 30 years old at the time, I know this because he told us.

I have never forgotten the day I gave him both barrels verbally, it was the outdoors PE lesson just after lunchtime on Tuesday 1st December 1998 and the lesson began at 1.30pm. The time is important here because he accused me of being very late arriving despite me not being late at all and perfectly on time and started arguing with me that the time was not actually half past one when it clearly was exactly half past one and I was wearing a watch that picked up an accurate time signal. Others were changing while I had this stand up argument. I'd never done anything like it before but to be so falsely accused was a total red rag to me and at 15 I was becoming far more confident of myself.

My PE teacher, Mr Hart-Booth simply would not back down with me and became intransigent. At one point I thrust my watch in his face quite close up to show him the accurate time and that I was not late to his PE lesson. I was continuing this argument standing in just my boxer shorts halfway through changing at one point when he told me to get the watch off my wrist that I shoved in his face, I shouldn't be wearing it. I actually shouted quite loudly and would not back down and even accused him of now wasting time and making the lesson late himself because of his unreasonable and wrong accusation to me. I even threatened him that if he kept on I would bring his behaviour towards me to the attention of his immediate PE superior, our head of PE and even the head teacher. It was the maddest I've ever been in school and almost anywhere else and one of those days when everything I said just came out of my mouth perfectly and well timed. Plus I was completely in the right anyway. If I'd even been 5 minutes late I'd have owned up and taken my telling off like anyone should.

So after this 2 minutes of madness which saw my PE teacher storming up and down the changing room while I followed him to make my point in his face, normal clothes off but PE kit not yet on, he suddenly went all silent on me and looked like he was sulking for the rest of a very uncomfortable lesson where very little further was said between us. It was not something I wanted to do but felt empowered by it afterwards. Nobody in class spoke a word about it. Not a single comment from anybody.

I thought I'd really gone and done it with firing off at a teacher like that so forcefully right in his face and that I was for the high jump and not the one in the school gym either. There was no swearing involved, the language was clean. I expected there to be some consequences but there was no punishment at all. Nothing.

I was brooding about it for something like 5 days and dreading his next lesson and I made sure to be more than on time and a bit early infact, dreading any kind of repeat performance. I had no history of being late or absent from any of his PE lessons.

What happened next was quite amazing. He took me aside quietly for a chat in a side room and that always spelled bad news for anyone if he did that. All of a sudden I was being given glowing praise as a great guy at school who he'd always trusted and did well, respected and liked a lot. It was everything I thought he didn't think about me and I even got a sort of apology. I almost didn't know how to react to it. It became clear he was one of those people who you can have a blazing row with and not only don't they hold it against you or see it as a slight on their authority figure status but that he actually held me in high regard for standing up for myself to him. Those type of people seem rare to me. From that moment on and for the time I had left at school we had a completely different teacher pupil relationship and it just seemed so much better as if the air had cleared. 25 years later he remains at my old school.

Taking on board your own story Greg2 I just wonder if anybody else has anything remotely similar to me here or even confronted a teacher openly which ended better than expected for them.

A couple of years ago while I was out walking the dogs a group of about eight men all looking under 45 came running past me bare bodied which was somewhat of a surprise on my regular haunt. I'd seen adult runners lots before in groups or alone but not like that. They looked like they were in serious training for something and almost like they were army or something but there is nothing like that anywhere near me at all so that was unlikely. Now I read on here that there is a bit of a barechest running craze going on in some quarters so possible I came across something like that going on.

But I was no stranger to that kind of thing myself. The area I walk the dogs is close to where I used to have to go doing school cross country and we had two teachers who took us out on a few occasions for a run consisting of a class full of barechest running lads during springtime about this time of year. Our cross country was more like a steeplechase where we had to jump fences and some minor water features along the way. We were certainly put through our paces back in the late 70s that's for sure.

It had its merits and was perfectly acceptable to me but it doesn't suit everyone.

All this about thinking you were too thin as a boy. I do understand being self-conscious at those ages, but for an active growing boy to be slender, with no excess weight, is perfectly normal during the school, growing years. Any Gym teacher who'd done a post graduate degree course in teaching, and to then specialise in physical education would surely have understood this. I think for many, it just gave another opportunity to humiliate, which seemed to be quite the routine for many Gym teachers. It does seem, from reading comments here, and remembering my own experiences, that the job certainly attracted types who would look for opportunities to give out bullying, or to just thoroughly enjoy being in charge…of young boys. Pathetic really, and some of the many wrong reasons to enter the profession. I was also very lean during all my school years, but I can't remember ever having to do a Gym lesson shirtless. We always had to wear our all white regulation kit.

I remember my Gym teacher being a very shouty, smallish man, who was also free at giving out the slipper. I do remember one very strange incident when we were all about 13. He was really having a go at one boy who was sitting diagonally across from me in the changing room. I didn’t catch how it all started, but we’d all just changed and were still sitting on the benches waiting to go into the Gym. All of a sudden this boy seemed to snap and swung a fist at him, and it then turned into a bit of a scuffle. We were all really shocked, as this lad was usually full of fun, but generally quite quiet. It seemed to end by the teacher just pushing him back down onto the bench, and then firmly instructing us all to stay where we were and to wait for the whistle; we would usually hear a whistle from within the Gym which was our signal to all go in. He then stormed off into the Gym, or maybe into his own little changing and shower room which was through a separate door off the Gym. There was then a several minute delay until we heard the shrill of the whistle to summon us all in.

I think this incident seemed to call his bluff, as he appeared just as unsettled by it all as we were shocked. He was also quite reasonable with us for the rest of the lesson, which was unusual for him. Nothing, as far as I can remember, was ever said about it again.

Bailey you were fortunate enough to have any part of your name used at all. In our school we had one or two PE teachers who cottoned onto some of the nicknames boys gave each other amongst themselves and started using them as well!

Ivan & Jason you are both spot on here.

I left school at the age of 17 after dropping out of sixth form halfway through. This was in 1989. I was just sick of the place by then and when an unexpectedly good job chance cropped up I jumped at it and took it, left school immediately and without any fanfare was gone.

As anyone who has stayed on after 16 at school in the past will know, you end up with quite a lot of these free periods throughout the week, so called study periods when not much studying was done. For many of them I wasn't even in the school grounds and just went home, nobody checked up. For one of these free periods each week we had to nominate one of them of our choice to do some PE, sometimes with other sixth formers and sometimes joining in with another lower aged class which you'd know nobody at all well.

Let me state it, I was never a fan of shirtless PE which I did have to do lots.

I loved eating anything but never put any weight on. Each week I worked out I must have walked at least 20 miles to and from school. My parents never drove me. I was a very thin schoolboy of normal height. But I occasionally found myself facing comments about how I looked, including teachers such as a time when I'd done something well and was grabbed by both my wrists, raising my arms high above my head and then looked at saying 'there's not much of you is there', something I was already very sensitive about because I tried hard to put a bit more weight and muscle on. PE that day was shirtless, quite a nightmare if you don't rate your body very highly. PE was spent shirtless at school roughly half the time up to 16. There never seemed to be any actual logic to why we went shirtless in some lessons and not others, it seemed completely random and not based on any specific reason.

It's a sorry state to have to admit this but at the age of 17 & 18 I'd spend ages looking at myself in the bathroom mirror worrying about my shape and weight thinking that I'd not developed properly in some way, no thanks to PE lessons and teachers throwaway comments about thin ones like me which played some part in how I saw myself and most importantly of all, how I thought everyone else was seeing me.